Drama as Pedagogy in

|

| ||||||||||||

|

It is my belief that at the heart of every teacher is an individual that yearns to engage their students in productive activity—activity that breaches the standardized testing of No Child Left Behind, the cinder-block worlds of traditional pedagogy, and, I dare say, Method. It is for this reason that I am interested in drama as a resource in the language classroom as well as drama as a transformative, human-making activity (Zafeiriadou, 2009; Via, 1978), with the potential to affect our personalities, adjust our codes of behavior (Hismanoglu, 2005; Livingstone, 1983), and mold our autonomy as individuals (Barnes, 1968). According to Via (1987), “Few would disagree that drama has at last established itself as a means of helping people learn another language. A great deal of our everyday learning is acquired through experience, and in the language classroom drama fulfills that experiential need” (p.110).

In answer to the question, why is drama relevant in today’s classroom; we can turn to a couple well-established trends in contemporary pedagogy: Post-Method pedagogy and Communicative Language Teaching. According to Kumaravadivelu (1994), second/foreign language pedagogy has made a shift from the conventional methods of classroom policy to a new world where “postmethod” is the norm. Teachers are no longer looking for an alternative method but rather an alternative to methods. This shift, as Kumaravadivelu puts it, “motivates a search for an open-ended, coherent framework based on current theoretical, empirical, and pedagogical insights” (p. 27) and he puts forth 10 macrostrategies for teachers to effect targeted learning outcomes:

It is my argument that the use of dramatic activities in the classroom can facilitate each of those macrostrategies. Nina Spada’s definitive work on the communicative approach in L2 teaching, which according to her has also reached a turning point (2007). According to Spada, communicative language teaching is “a meaning-based, learner-centered approach to L2 teaching where fluency is given priority over accuracy and the emphasis is on the comprehension and production of messages, not the teaching or correction of language form” (p. 272). The learner is now seen as an active participant in the process of language learning and teachers are expected to develop activities to promote self-learning, group interaction in real situations and peer-teaching (Sam, Wan Yee, 1990). I elevate drama as a means to achieve this end. Also central to Spada’s work was that “language proficiency is not a unitary concept but consists of several different components” (Spada, 2007, p. 273), including linguistic competence, pragmatic knowledge, information on the socio-linguistic appropriateness of language, and strategic competence or compensatory strategies with the recommendation that L2 pedagogy should include all components in its curriculum. For these reasons, drama is most aptly suited for the second language classroom. |

"Drama is a transformative, human-making activity with the potential to affect our personalities, adjust our codes of behavior and mold our autonomy as individuals." |

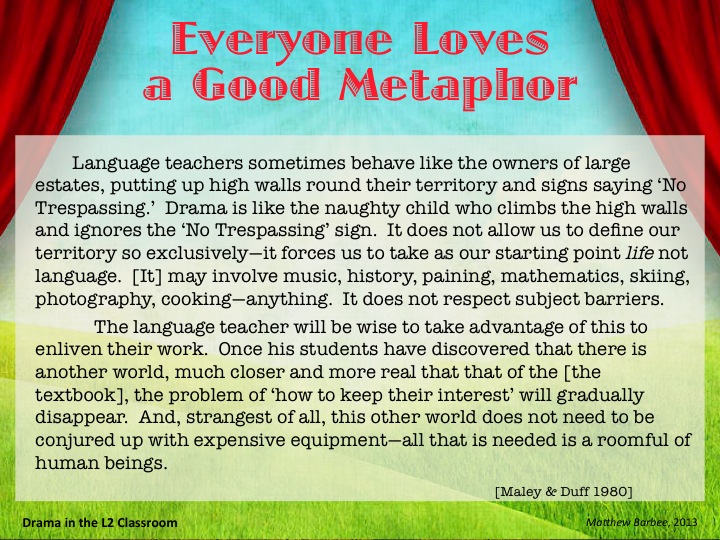

Drama vs. TheatreDrama. Interaction between two or more people that conveys meaning. It is process rather than product that is the focus of drama. (Holden 1981, Via 1987, Zafeiriadou 2009)

Theatre. Interaction between people for the benefit of other people. It must also convey meaning among the performers and between the performers and the audience. (Holden 1981; Via 1978, 1987) Dramatic Activities. Strategies to achieve either drama or theatre. (Via 1987) They are dramatic because they draw on the unpredictable power generated when one person is brought together with others. Each student brings a different life, a different background into the class. (Haley & Duff 1978, 2011) Theatre arises as a product of the drama process and drama becomes theatre when the process becomes performance. The two tend to merge and boundaries are often blurred as drama work often contains an element of theatre - and theatre always contains drama! For theatre and drama to work effectively, the product needs to be a separate entity and there should be a clear demarcation between the 'performance' that is theatre and the 'experience' that is drama. Theatre also exists when an audience observes and responds to the product being revealed. As adults, we have all spent a great deal of our lives involved in drama or theatre: the action rhymes and songs we took part in at nursery school; the games we played as children; the elaborate 'performances' we gave to our parents and teachers as teenagers; the roles we play at work and at home. Our basic need is to communicate, to connect with others, and drama forms the foundation of that need. Theatre continues to inform our behavior in the work place: role-playing, presenting an image and improvisation are second nature to us. Drama and theatre are inexorably intertwined with how we live our lives and how we relate to other people; structured drama and theatre applications recognize this - and build on it. |

Benefits of Drama

in the L2 Classroom [adapted from Haley & Duff 1978, 2011]

|

Dramatic Activities for the Classroom

Simulation

Hot-seating

- Dramatic, communicative activities that ask students to solve a problem as themselves. (Livingstone 1983, Via 1987) Synonymous with task-based language teaching.

- (1) Students are told that they are on a deserted island and can only bring three items. They have to form groups and and take their three items into the group with them. New rule: the group can only keep three items total on the island. They must decide which three items they want to keep through discussion and negotiation. As a group they present to the class which three items they chose and why.

- An extension of simulation where students are asked to take on different personas other than themselves with motivations and attitudes matching those new personas. (Livingstone 1983)

- (1) Click for my page of Role-Playing Lessons and Videos I have made while teaching in Japan.

- (2) Click for an example of a role-play scenario: heatwave

- (3) Click for an example of business and work related role-playing scenarios.

Hot-seating

- Interviewing a character or role-player who remains 'in role.’ Group and teacher can ask questions. This may be done by freezing the improvised action and removing the characters, or by sitting them formally on the 'hot-seat' to face questioners.

- Encourages insights into character and roles, highlighting motivations and personality, and reflective awareness or human behavior.

- (1) Students place the teacher on the 'hot-seat' to respond to questions in a role taken from a storybook they are reading.

(2) The teacher or a student in the role of Goldilocks is placed on the 'hot-seat' to explore her reasons for entering the bear's house without being invited.

(3) In a drama about playground bullying, the action is frozen in the middle of a playground scene and the school bully is 'hot-seated' in order to explore his or her motives more fully by questions from the class.

- The teacher stimulates and directs the drama from within by adopting a suitable role. This can excite interest, control the action, incite involvement, provoke tension, challenge superficial thinking, create choices and ambiguity, develop the narrative and create possibilities for the group to interact in role.

- Removes some degree of power and status from the teacher but replaces it with negotiated role relationships.

- (1) The teacher takes the role of a senior citizen taking a pet to an animal welfare center, with the children in role as vets. The drama explores how the pet can be cared for.

(2) The teacher takes the role of a market owner who wants to shut down part of the market, as the area is dangerous and some stalls must be moved on to prevent the ground subsiding. The children adopt roles as market stallholders.

(3) The teacher takes the role of a refugee who does not speak English and who wants to contact her family in a different land. The children try to find a means of communicating and helping.

- Children work in small groups to plan, prepare and present improvisations as a means of expressing understanding of a situation, idea or experience.

- Requires excellent negotiating skills on the part of the participants.

- Good for sequencing ideas, selecting content, exploring characterization, devising dialogue and events, gaining performance skills and developing confidence in expressive performance.

- (1) The students create scenes relating to Christmas morning - opening presents, playing with toys or watching television, for example.

(2) The students create scenes which reveal the problems the elderly have in the winter.

(3) In a situation in which the students have been exploring loneliness, they are asked to improvise a scene that shows some old people sitting in an old people's home, discussing their feelings about the past and the future.

- At a key moment in the drama, selected by the teacher, children take on roles representing a different status, viewpoint or occupation.

- This is an effective convention for examining social interaction, opposing viewpoints, relationships and motives.

- (1) In a drama about a toy shop all the children are in role as toys, talking about the big sale which is to start the next day. The teacher then reverses the roles and asks them to be parents and children attending the sale, talking about which toys they can afford and which ones they are thinking of buying.

(2) In a drama about a polluted sea, the children are first in role as fishermen who need the sea to survive. They then go into role as workers at the factory which is causing the pollution by pouring waste into the sea.

(3) In a drama about an unexploded bomb found underneath a school, the children a first in role as villagers who have to evacuate their homes for safety. They then go into role as the councilors who know that the bomb might destroy the whole village, but who are pretending that everything is under control.

- Individual students, in role, speak their inner thoughts. The teacher freezes the drama and taps a chosen character on the shoulder to indicate that they should speak their thoughts or feelings within the drama.

- Thought-tracking slows the action down by allowing it to pause, enables the children to reflect on events and establishes what the characters are thinking or feeling at a specific moment in the drama - which may or may not reflect what they have been saying out loud.

- (1) The students all have similar roles, such as children on a visit to the zoo. They see an elephant that is hurt and the teacher asks them to describe what they are feeling as they look into the elephant's area at the zoo.

(2) With the whole class in role as Goldilocks, miming her journey through the woods to visit the bear's house, the teacher freezes the action to ask individual Goldilocks whether they know they are doing wrong, and why they don't feel they should return to the path.

(3) In the middle of a drama about a mining accident, the miners of the village can be asked to say what they feel as they create a still-image at the pit-head, waiting for news.

|

Other Dramatic Activities

|

Other Product-centered Dramatic Activities

|

Slides from Presentation

References

Other Resources

Online Resources

- Barnes, D. (1968). Drama in the English classroom. Champaign, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

- Holden, S. (1981). Drama in language teaching: Longman handbook for language teachers. London, Great Britain: Spottiswoode Ballantyne Ltd.

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The postmethod condition: (E)merging strategies for second/foreign language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1), 27-48.

- Livingstone, C. (1983). Role-play in language learning: Longman handbooks for language teachers. Singapore: The Print House Ltd.

- Maley, A., & Duff, A. (1978, 2011). Drama techniques: A resource book of communication activities for language teachers (3rd Edition). In P. Ur (Series Ed.), Cambridge Handbooks for Language Teachers, Cambridge: CUP.

- Spada, N. (2007). Communicative language teaching: Current status and future prospects. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 271-288). New York: Springer.

- Via, R. A. (1976). English in three acts. HongKong: The University Press of Hawaii.

- Via, R. A. (1987). “The magic if” of theater: Enhancing language learning through drama. In W. M. Rivers (Ed.), Interactive Language Teaching (pp. 110-123). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zafeiriadou, N. (2009). Drama in language teaching: A challenge for creative development. Issues, 23, 4-9.

Other Resources

- Bolton, G. (1992). New perspectives on classroom drama. Great Britain: Simon & Schuster.

- Boal, A. (1993). Theatre of the oppressed, New York: Theatre Communications Group.

- Burke, A. & O’Sullivan, J. C. (2002). Stage by stage: A handbook for using drama in the second language classroom, New York: Heinemann Drama.

- Jones, K. (1982). Simulations in language teaching, Cambridge: CUP.

- Kaplan, S. (Ed.). (2011). Teaching drama in the classroom, Boston: Sense.

- Malkoc, A. M. (1993). Easy plays in English, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Rathburn, A. K. (2000). Taking center stage: Drama in America. In S. M. Gass & A. L. Tickle (Series Eds.), The Michigan State University textbook series of theme-based content instruction for ESL/EFL, Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P.

- Watcyn-Jones, P. (1988). Act English, New York: Penguin Books.

- Whiteson, V. (1996). New ways of using drama and literature in language teaching. In J. C. Richards (Series Ed.), New ways in TESOL series II: Innovative classroom techniques, Bloomington, IL: TESOL, Inc.

- Whiteson, V., & Horovitz, N. (2002). The play’s the thing: A whole language approach to learning English. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Winston, J. (Ed.). (2012). Second language learning through drama: Practical techniques and applications, London: Routledge.

Online Resources